Showing Posts by Date: 09/2018

09.28.2018

No other city felt the AIDS crisis more deeply than New York City. New York City was the first city in North America to have confirmed infections and by the mid-1980s, nearly 2,000 New Yorkers had died from AIDS and another 1,800 had been diagnosed. The most affected by the illness were those who at the fringes of society. Due to discrimination, gay men, intravenous drug users, and people of color provoked little sympathy or support from the public or financial support from the government. Meanwhile, for those who were living with AIDS, the costs of medication, the physical toll, and discrimination and stigma around the disease made maintaining housing extremely difficult. As a result, a number of those living with HIV/AIDS became homeless.

No other city felt the AIDS crisis more deeply than New York City. New York City was the first city in North America to have confirmed infections and by the mid-1980s, nearly 2,000 New Yorkers had died from AIDS and another 1,800 had been diagnosed. The most affected by the illness were those who at the fringes of society. Due to discrimination, gay men, intravenous drug users, and people of color provoked little sympathy or support from the public or financial support from the government. Meanwhile, for those who were living with AIDS, the costs of medication, the physical toll, and discrimination and stigma around the disease made maintaining housing extremely difficult. As a result, a number of those living with HIV/AIDS became homeless.

In 1983, the AIDS Resource Center was founded. Later renamed Bailey House, the AIDS Resource Center had a particular focus on the importance of housing for people living with AIDS. The AIDS Resource Center created an innovative model, its Supportive Housing Apartment Program (SHAP). SHAP brought supportive services to the homes of people living with AIDS and helped them to maintain stability in their lives. This was the nation's first scattered site housing for people living with HIV/AIDS; it created a model of supportive housing that has since been replicated internationally.

In the face of mounting public pressure from groups like Gay Men’s Health Crisis and the AIDS Resource Center, in 1985, under Mayor Ed Koch, the Human Resources Administration created the Division of AIDS Services and Income Support (DASIS), which later became the HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA). DASIS provided rental vouchers for homeless and very low-income New Yorkers with AIDS, enabling them to bypass the shelter system and access housing, affordable or supportive, directly.

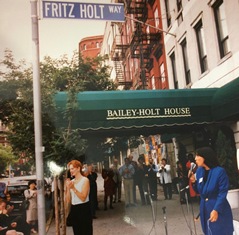

In 1986, with the support of the Koch and Cuomo administrations, the AIDS Resource Center opened Bailey-Holt House, the nation’s first congregate residence for people living with AIDS. This program became a shining example, proving that stable, supportive housing helped people with AIDS maintain their health and dignity, and led to housing becoming a demand of AIDS activists in New York City and around the nation. Today, Bailey House operates housing for nearly 700, women and children across New York City.

In 1990, the Federal government created the Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) program in the AIDS Housing Opportunities Act, a part of the Cranston-Gonzales National Affordable Housing Act of 1990. HOPWA provided housing assistance and supportive services for low-income and homeless people living with HIV/AIDS, and their families. This was the first significant federal funding for HIV/AIDS housing, and this funding stream continues to be a vital source of services dollars nationally.

As public understanding of the disease increased, the programs to support those with HIV/AIDS gained broader public support. In NYC, the dedicated nonprofit community, including Housing Works, Harlem United, Bailey House, Volunteers of America of Greater New York, Comunilife, and others, continued to construct congregate supportive housing for people living with HIV/AIDS with the help of the City’s Supportive Housing Loan Program, and state Homeless Housing Assistance Program (HHAP) funding. In 2007, the NY/NY III agreement provided a new dedicated source of services funding from the City and State for new congregate and scattered site housing for people living with HIV/AIDS.

In 2016, in a program called “HASA for All,” Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that low-income residents of NYC who are HIV-positive but asymptomatic would be able to access the same assistance as low-income residents who show symptoms. About 6,500 to 7,000 additional people are now able to benefit from the expansion of HASA, which now serves about 32,000 people.

In 2016, in a program called “HASA for All,” Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that low-income residents of NYC who are HIV-positive but asymptomatic would be able to access the same assistance as low-income residents who show symptoms. About 6,500 to 7,000 additional people are now able to benefit from the expansion of HASA, which now serves about 32,000 people.

To this day, nonprofits in NYC and NYS continue to develop supportive housing to ensure that people living with HIV/AIDS have access to high quality homes and the services they need to maintain their lives in stability and dignity.

09.27.2018

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) was created in 1986 under President Reagan and made permanent in 1993 under President Clinton, around the same time that the supportive housing model was scaling up in New York. (The first New York/New York agreement was signed in 1990). Created through the federal Tax Reform Act, LIHTC ushered in a new era of affordable and supportive housing development, one that engaged and expanded the field of stakeholders and leveraged private investment.

What is the Low Income Housing Tax Credit?

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit is an indirect federal subsidy for low-income affordable rental housing. The program, administered by the U.S. Department of Treasury, acts as an incentive to private developers and investors to provide low-income housing. LIHTC provides a dollar-for-dollar credit against federal income tax liability, meaning for every tax credit you claim, you can reduce your federal tax bill by one dollar. Investors make a cash contribution, which functions as equity for a real estate deal, in exchange for future allocation of tax credits.

Pools of LIHTC are allocated to states based on a federal formula. In New York, NYS Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) and NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) have the authority to provide tax credits according to local priorities.

How does it help create supportive housing?

Before the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, supportive housing was entirely financed by grants and subsidized loans from the government. By enabling public-private partnerships, LIHTC brought new resources to the table.

In the early 1990s, LIHTC was first used to finance the rehabilitation of nine buildings in New York City to become supportive housing for low-income individuals and those who had experienced homelessness. In a process known as syndication, National Equity Fund and Enterprise helped nonprofit developers access LIHTC and connect their projects to investors.

LIHTC Today

Today, LIHTC helps finance the majority of supportive housing in New York State. 73% of the residences that opened in 2017 used the credit. The Network and our partners are deeply involved with efforts to expand and strengthen the program, including advocating that Congress pass the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act.

|09.26.2018

Housing First is a unique approach to provide housing to those who have been chronically homeless without any preconditions of sobriety, treatment programs or service participation. Watch Kevin O'Connor, Executive Director at Joseph's House & Shelter, discuss the success of this approach in supportive housing.

|09.25.2018

The world-renowned HPD Supportive Housing Loan Program (SHLP)– a one-stop shop that provides loans to develop supportive housing in New York City – had humble beginnings. It was started in 1988 and combined the Capital Budget Homeless Housing Program (CBHHP) and the Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Loan Program which at the time was financing the renovation of commercial SROs. Under Tim O’Hanlon during his time at the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the newly imagined SRO Loan Program grew to be the primary program the City uses to house chronically homeless New Yorkers.

The early Supportive Housing Loan Program (then SRO Loan Program) projects were exclusively existing buildings. The program either renovated or rehabilitated the buildings so that 60% of the apartments served people in need of both housing and onsite services – such as formerly homeless individuals coping with behavioral health issues – and 40% of the apartments were designated for low-income individuals from the community. The supportive/affordable mix had numerous benefits including creating or preserving affordable housing, providing a community benefit, and ensuring buildings were integrated.

The early Supportive Housing Loan Program (then SRO Loan Program) projects were exclusively existing buildings. The program either renovated or rehabilitated the buildings so that 60% of the apartments served people in need of both housing and onsite services – such as formerly homeless individuals coping with behavioral health issues – and 40% of the apartments were designated for low-income individuals from the community. The supportive/affordable mix had numerous benefits including creating or preserving affordable housing, providing a community benefit, and ensuring buildings were integrated.

Another key element of the Program was its reliance on nonprofits: “When the City started to try to develop homeless housing on its own, parallel to CBHHP, there was too much community resistance. But when local nonprofits developed, the community went for it. They liked the accountability and the accessibility; the organizations were right there in their communities already,” said Tim O’Hanlon, Vice President, Hudson Housing Capital and Former Assistant Commissioner of Special Needs Housing, HPD.

Emily Lehman, current Assistant Commissioner of Special Needs Housing, adds,“SHLP is really geared toward working with NFPs; this is a hallmark of what SHLP has always been about. The nonprofit advocate community created supportive housing in NYC, so we have tried to preserve their role to this day. One of the things that I really love about working in this program is that it feels like [the nonprofits and HPD] are all on the same team, working towards the same goal.” For-profit developers can now develop supportive housing if in joint venture with a nonprofit, further expanding the universe of actors who can work to bring supportive housing to fruition.

Emily Lehman, current Assistant Commissioner of Special Needs Housing, adds,“SHLP is really geared toward working with NFPs; this is a hallmark of what SHLP has always been about. The nonprofit advocate community created supportive housing in NYC, so we have tried to preserve their role to this day. One of the things that I really love about working in this program is that it feels like [the nonprofits and HPD] are all on the same team, working towards the same goal.” For-profit developers can now develop supportive housing if in joint venture with a nonprofit, further expanding the universe of actors who can work to bring supportive housing to fruition.

The Program allowed providers to take on massive projects, gut rehabbing dilapidated SROs and hotels, around the city, primarily in the Upper West Side and in the Times Square area. The largest project was the Times Square Hotel. Rosanne Haggerty, former Executive Director of Common Ground (now Breaking Ground) submitted an application to HPD seeking to rehabilitate the former hotel that had been used to provide degraded housing to up to 1,000 tenants becoming in what was known as a “welfare hotel” in the 1980s. Tim O’Hanlon remembers: “At the time no one was spending money to buy buildings. But the City agreed to give Common Ground $30 million to acquire the Times Square Hotel.”

The first completely newly constructed supportive housing residence was not built until the mid-1990s. Around the same time, the financing structure for supportive housing deals were beginning to diversify. SHLP funding was paired with 9% Low Income Housing Tax Credits for the first time. In 2018, HPD set-aside 40% of its 9% tax credits to fund supportive housing in New York City.

Former HPD Associate Commissioner Jessica Katz commented on the program’s flexibility and its role in building the capacity of the nonprofit development community: “Nowhere else is there a program for supportive housing that operates at this scale. One key aspect is that SHLP can operate both as a stand alone program as well as in concert with other mainstream affordable housing resources. This ensures a diversity of projects including smaller deals with smaller nonprofits as well as the ability to incorporate supportive housing within larger affordable housing projects. This builds capacity in the sector and encourages a wide variety of supportive housing options.”

Former HPD Associate Commissioner Jessica Katz commented on the program’s flexibility and its role in building the capacity of the nonprofit development community: “Nowhere else is there a program for supportive housing that operates at this scale. One key aspect is that SHLP can operate both as a stand alone program as well as in concert with other mainstream affordable housing resources. This ensures a diversity of projects including smaller deals with smaller nonprofits as well as the ability to incorporate supportive housing within larger affordable housing projects. This builds capacity in the sector and encourages a wide variety of supportive housing options.”

Since 1988, the Supportive Housing Loan Program and related historic HPD programs have produced over 19,000 supportive and affordable units.

09.24.2018

True Colors Residence (TCR), a project of West End Residences, was the first permanent supportive housing for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) youth with a history of homelessness. This profoundly underserved population is estimated to make up nearly 40% of homeless youth in New York City. Opening in September 2011 in Harlem, it offers 30 units of supportive housing for formerly homeless LGBTQ New Yorkers aged 18-24.

True Colors was developed in partnership with Grammy-award winning artist Cyndi Lauper and her manager, longtime West End Residences volunteer Lisa Barbaris. It arose from a simple question: What can nonprofits do to help LGBTQ homeless youth in New York City? Lauper discussed the issue with her manager Lisa Barbaris and then Executive Director of West End Residences, Colleen Jackson. The three arrived at a bold, untried solution: supportive housing.

"I'm lost for words; I'm so happy right now," said Priscilla Rumnit, one of the building’s tenants. "I’m just so excited for this place. Here, I know that I'm safe.”

True Colors in Harlem was just the beginning of the legacy of West End Residences to provide housing to the LGBTQ homeless youth. A second True Colors Bronx opened doors in 2015 and West End Residences has plans to open up a True Colors in all five boroughs of New York City.

09.21.2018

In 2002, The Network put down roots in Albany to become more effective in its statewide advocacy efforts and to grow the supportive housing movement beyond New York City. Watch the video above to hear from our two staff members about the importance of The Network going statewide!

|09.20.2018

In 2001, in collaboration with the Corporation for Supportive Housing, a research team from the University of Pennsylvania published the first-ever study to measure the impacts of supportive housing. It was the most comprehensive study to date on the effects of homelessness and service-enriched housing on mentally ill individuals’ use of publicly funded services.

Titled "Public Service Reductions Associated with Placement of Homeless Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Supportive Housing," It tracks the public service use of 4,679 homeless, mentally ill New York City residents from 1989 to 1997. The “Culhane Report,” as it’s often referred to, quantifies costs of both homelessness and supportive housing. It does this by comparing how frequently homeless people and supportive housing tenants use services such as psychiatric inpatient care and emergency rooms.

Dennis Culhane and his coauthors calculate that a homeless, mentally ill person on the streets of New York City costs taxpayers $40,451 a year -- in 1999 dollars. Supportive housing reduces these annual costs by a net $16,282 per housing unit. This study was written by Dennis P. Culhane, Stephen Metraux and Trevor Hadley.

09.19.2018

In November 2005, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Governor George Pataki signed NY/NY III, committing to create 9,000 units of supportive housing for a variety of disabled homeless people in New York City over ten years. The Agreement marked the largest commitment to creating housing for homeless people in the nation's history.

The NY/NY III Supportive Housing Agreement was larger and more comprehensive than its predecessors, with a ten-year goal of creating 9,000 units of supportive housing : 6,250 units of new supportive housing and subsidize 2,750 scattered-site supported housing units in existing buildings.

With ten City and State government agencies signing NY/NY III and an additional three unofficial but critical agencies participating, the Agreement brought about unparalleled interagency collaboration all focused on the goal of reducing chronic homelessness.

The first two NY/NY agreements provided housing and services solely for individuals with mental illness. This third agreement expanded the housing and services to tenant populations with a variety of special needs. New target populations include families with serious and persistent mental illness (SPMI) and medical disabilities, youth aging out of foster care or leaving psychiatric facilities, and individuals with substance abuse, both active and in recovery.

NY/NY III’s prescriptive nature – laying out how many and what type of units (scattered site or congregate) were to be created for each population – helped ensure that the participating agencies would meet the Agreement’s timeline and funding needs.

The linking of dependable rental subsidies and service funding to support the capital investment created a name recognition with NY/NY III that allayed investors’ concerns about housing extremely low-income, disabled tenants.

NY/NY III commitment jumpstarted and increased the volume of supportive housing development. In turn, the agreement’s scope increased the supportive housing community’s development capacity: thirty new nonprofits began to build supportive housing in the city – a 60% increase in the number that had been developing before.

Prior to NY/NY III, only one for-profit affordable housing developer collaborated with nonprofits to develop supportive housing. The size and scope of NY/NY III however helped spawn eighteen joint ventures.

Focus on chronic homelessness led to an early decrease among street homeless of 49%

NY/NY III called for and funded an ongoing multi-tiered evaluation of the commitment. The first interim report published by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene found that the early years of implementation led to a cost savings across systems of $10,100 per person.

Read the Network's Taking Stock of NY/NY III for more information.

|09.18.2018

Supportive Housing provides our most vulnerable neighbors a life of dignity and support. The St. Francis Residences were founded in the early 1980’s by the Fathers John who found a way to house and provide care to homeless New Yorkers who were suffering from mental illnesses.

|09.17.2018

WSFSSH's Laura Jervis (left); St. Francis Friends of the Poor's Father Tom, Fathers John (center); Broadway Housing Community's Ellen Baxter (right).

Supportive housing had a number of mothers and fathers, all of whom were trying to help the most vulnerable New Yorkers — homeless people, people living with mental illness, the elderly, and those living the most marginalized lives — and who were all, simultaneously, coming to the same conclusion: to make a difference in the lives of the people they cared about, they could no longer just provide services. Somehow they would also need to figure out how to provide them with housing AND services.

It is hard to imagine now that there was no such thing as widespread homelessness in New York City before the late 70s. Sure, there were homeless people, but nothing like what happened when massive amounts of "housing of last resort," including rundown Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing and dilapidated hotels, were knocked down at an alarming rate to make room for market rate housing. Since the 60s, deinstitutionalization had meant that tens of thousands of people who had only lived in psychiatric institutions joined the ranks of other very vulnerable individuals who were living in whatever housing they could afford. As this housing disappeared, people with the least resources found themselves with nowhere to go. Suddenly there were people sleeping on the streets everywhere and elderly women pushing grocery carts with their worldly goods inside.

Ellen Baxter (second row, third from left)

Advocates across the City began fighting for the most basic forms of housing, finally winning a seminal victory in the courts with the Callahan decree in 1981 guaranteeing homeless New Yorkers a right to shelter. Meanwhile, Ellen Baxter, and Kim Hopper went into the streets to interview homeless people sleeping in public places and found that many homeless New Yorkers needed more than shelter to thrive: they also needed easy access to an array of social services.

This was the conclusion that many others were coming to experientially on their own. Laura Jervis was seeing (and abhorring) the term “bag ladies” all over the Upper West Side. Elizabeth Stetcher Trebony was seeing the same thing for elderly people in Midtown. Fathers John McVean and John Felice were ministering to poor people living in SROs in Chelsea, only to find that a huge number of them had come from living in psychiatric institutions. And Stephan Russo was seeing poor tenants on the Upper West Side lose their housing to gentrification. All of these individuals were organically moving toward the same solution to all these problems — own the housing and provide necessary services.

Stephan Russo, John Tynan, Bill Traylor, Elizabeth Trebony

Ms. Trebony, who went on to create Project FIND was the first to begin the process of buying and rehabbing an old SRO and turning it into supportive housing although completing the task of turning the old Woodstock Hotel into supportive housing ended up taking nearly two decades. So the first pioneers to actually buy a building, rehab it and offer services to the most vulnerable were Father John McVean and Father John Felice of St. Francis Friends of the Poor.

The Fathers John ran the Thursday bread line at their church on 31st Street where they met many residents from the Aberdeen, an SRO in terrible disrepair one block away. As Father McVean did outreach to seniors at the Aberdeen, he discovered that there were also 150 deinstitutionalized people from psychiatric institutions, causing him to cobble together a group of volunteers to provide onsite psychiatric and social work services to residents. All went well with “The Aberdeen Project” until the owners decided they wanted to convert it into a tourist hotel.

With the imminent eviction of the vulnerable people with whom they had been working so closely, the Fathers John sat down one evening, each with a glass of scotch, put up their feet, and said "let’s buy our own hotel" having, of course, no idea what that entailed.

Father John Felice at signing of the NY/NY Agreement; Father John McVean (left) and Father John Felice (right)

They soon found out. With the help of friends and supporters, they found a building on East 24th Street and raised enough money to buy it. Their Provincial administration then provided the money needed for renovations, HRA, OMH and psychiatric staff from Bellevue provided on site services. So it was that on November 24th, 1980, the first St. Francis Residence opened and the first supportive housing was born.

Ms. Trebony, in the meantime, started Project FIND as part of a national demonstration project on elderly advocacy and was an early vocal opponent of the destruction of West Side SROs. In 1975, the agency obtained a management and operating lease on the Woodstock Hotel, a former luxury hotel located in the heart of Times Square that had fallen into deplorable condition with only 80 of its 320 rooms habitable. Through the blood, sweat, and tears of hundreds of federally funded low-income city workers in the CETA Maintenance program, Project FIND rehabilitated the building from a nearly abandoned eyesore into permanent housing for over 200 seniors. A Senior Center on the second floor of the hotel was added in 1977 which included a social service case management component. Project FIND purchased the building in 1979 but the struggle to make it fully habitable extended until 1995.

Meanwhile, Ellen Baxter was meeting with and following in the footsteps of the Fathers John. She formed a new nonprofit called the Committee for The Heights Inwood Homeless (CHIH) (now called Broadway Community Services) designed to provide a secular model that garnered investment from every level of government.

In the early 1980s, CHIH transformed an apartment building on West 178th Street into 55 units of supportive housing finally opening in 1986. While the St. Francis residences had relied on simple financing packages, renovation of this building, known as “The Heights,” required an extremely complex combination of funding sources, including a low interest HPD Participation Loan from the city (for capital and acquisition costs), a state Special Needs Housing Act grant, private bank loans, and federal tax credits.

Ellen Baxter (left) and Tony Hannigan (third from right and above)

Operating costs for The Heights were subsidized through a new federal subsidy which provided rental support for low-income tenants. But the Heights introduced another innovation: the notion of partnering with another non-profit to provide onsite services. Those were to come from a partnership with Columbia University Community Services (CUCS) (now called the Center for Urban Community Services).

CUCS President & CEO Tony Hannigan’s story began a few years out of graduate school in 1981 when, he was tasked with a field initiative of locating vulnerable homeless single people staying in SROs — and remembers that 40% of SRO housing stock had been lost to gentrification at that time. As Ellen was working on transforming the Heights, CUCS applied to the Department of Mental Health to provide services to the tenants.

Another motivating force behind the birth of supportive housing was coming from communities’ desire to preserve and revitalize what they perceived as rapidly disappearing affordable housing. Thus, in 1981, when the West 87th Street Block Association heard that a deteriorating SRO, Capitol Hall, might be replaced with luxury housing, they approached Goddard Riverside Community Center and The Settlement Housing Fund to help preserve it. Goddard purchased the property in 1983 and started rehabbing it the following year into 202 supportive housing units.

Meanwhile, also on the Upper West Side, Laura Jervis was doing outreach to elderly people living in SROs there, having recently graduated from seminary. The now-retired West Side Federation for Senior and Supportive Housing (WSFSSH) Executive Director witnessed first-hand the fear people had to leave their rooms and the impact of isolation on elderly communities. She formed a coalition of community groups and religious institutions from the West Side to help these individuals, and WSFSSH was born. Their first building was The Marseilles, which Laura insisted on staffing with a social worker. “It’s hard to imagine today, but having social services on-site in senior housing was a radical idea in 1980!”

Laura Jervis maintains that seniors and those who have experienced the trauma of homelessness need more than just housing — her advocacy message from the start. “Over the years, in all of our buildings, it is the sense of community that is developed by residents and staff that has been the key to the success of our mission.”

Among the most ambitious and prolific early adopters of supportive housing in the early 1980s was Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens who melded their mission of serving the most vulnerable and combined it with the Church’s significant real estate portfolio by converting three vacant schools and a convent into 225 units of supportive housing called Caring Communities. The organization put together twelve separate funding sources to finance the project, including an HPD Participation Loan, federal Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation rental support and state Homeless Housing Assistance Program funding.

Another significant contribution from Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens was as a crucible for a generation of powerful advocates: Executive Director John Tynan had the great good fortune to have Bill Traylor, Connie Tempel, and Laura Mascuch all working for him in housing development or management.

As these buildings were opening, however, the question of who could live in them came to the forefront. Thus, in the mid-1980s, Stephan Russo of Goddard Riverside Community Center called together other early pioneers to ensure that homeless neighbors and community members were going to continue to be served in this new model of housing, leading to the now-normal 60/40 mix of individuals referred from the shelters and low income individuals from the community. The coalition became the SRO Providers Group, which then met regularly to share promising strategies and to lobby city and state government in a single, unified voice.

The SRO Providers Group evolved into the Supportive Housing Network of New York.

| New York State, New York City, Member News, Network Events