The Founders of the Supportive Housing Movement

Father John Felice at the podium (left) and the founders of the supportive housing movement (right).

Supportive housing had a number of mothers and fathers, all of whom were trying to help the most vulnerable New Yorkers—homeless people, people living with mental illness, the elderly, and those living the most marginalized lives—and who were all, simultaneously, coming to the same conclusion: to make a difference in the lives of the people they cared about, they could no longer just provide services. Somehow they would also need to figure out how to provide them with housing.

It is hard to imagine now that there was no such thing as widespread homeless-ness in New York City before the late 70s. Sure, there were homeless people, but nothing like what happened when massive amounts of ‘housing of last resort’ including rundown Single Room Occupancy housing and dilapidated hotels were knocked down at an alarming rate to make room for luxury housing. Since the 60s, deinstitutionalization had meant that tens of thousands of people who had only lived in psychiatric institutions joined the ranks of other very vulnerable individuals who were living in whatever housing they could afford. As this housing disap-peared, people with the least resources found themselves with nowhere to go: suddenly there were people sleeping on the streets everywhere and elderly women pushing grocery carts with their worldly goods inside.

Ellen Baxter (second row, third from left)

Advocates across the City began fight-ing for the most basic forms of housing, finally winning a seminal victory in the courts with the Callahan decree in 1981 guaranteeing homeless New Yorkers a right to shelter. Meanwhile, Ellen Baxter and Kim Hopper went into the streets to interview homeless people sleeping in public places and found that many homeless New Yorkers needed more than shelter to thrive: they also needed easy access to an array of social services.

This was the conclusion that many others were coming to experientially on their own. Laura Jervis was seeing (and abhorring the term) “bag ladies” all over the Upper West Side. Elizabeth Stetcher Trebony was seeing the same thing in Midtown. Fathers John McVean and John Felice were ministering to poor people living in SROs in Chelsea, only to find that a huge number of them had come from living in psychiatric institutions. And Stephan Russo was seeing poor tenants on the Upper West Side lose their housing to gentrification. All of these individuals were organically moving toward the same solution to all these problems – own the housing and provide necessary services.

Elizabeth Stetcher Trebony (left)

Ms. Trebony, who went on to create Project FIND was the first to begin the process of buying and rehabbing an old SRO and turning it into support-ive housing although completing the task of turning the old Woodstock Hotel into supportive housing ended up taking nearly two decades. So the first pioneers to actually buy a building, rehab it and offer services to the most vulnerable were Father John McVean and Father John Felice of St. Francis Friends of the Poor.

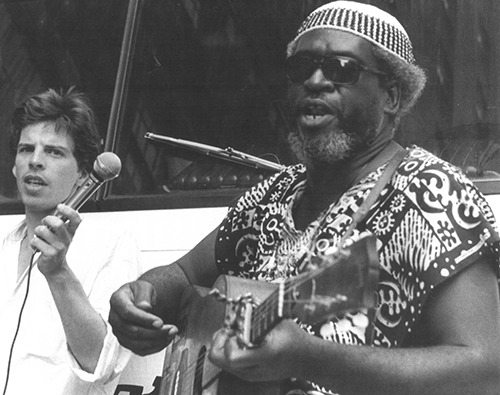

Father John Felice (center) and Father John McVean (far right)

The Fathers John ran the Thursday bread line at their church on 31st Street where they met many residents from the Aberdeen, an SRO in terrible disrepair one block away. As Father McVean did outreach to seniors at the Aberdeen, he discovered that there were also 150 deinstitutionalized people from psychiatric institutions, causing him to cobble together a group of volunteers to provide onsite psychiatric and social work services to residents. All went well with “The Aberdeen Project” until the owners decided they wanted to convert it into a tourist hotel.

With the imminent eviction of the vulnerable people with whom they had been working so closely, the Fathers John sat down one evening, each with a glass of scotch, put up their feet, and said ‘let’s buy our own hotel’ having, of course, no idea what that entailed.

Father John McVean (left) and Father John Felice (right)

They soon found out.With the help of friends and supporters, they found a building on East 24th Street and raised enough money to buy it. Their Provincial administration then provided the money needed for renovations, HRA, OMH and psychiatric staff from Bellevue provided on site services. So it was that on November 24th, 1980, the first St. Francis Residence opened and the first supportive housing was born.

Ms. Trebony, in the meantime, started Project FIND as part of a national demonstration project on elderly advocacy and was an early vocal opponent of the destruction of West Side SROs. In 1975, the agency obtained a management and operating lease on the Woodstock Hotel, a former luxury hotel located in the heart of Times Square that had fallen into deplorable condition with only 80 of its 320 rooms habitable. Through the blood, sweat, and tears of hundreds of federally funded low-income city workers in the CETA Maintenance program, Project FIND rehabilitated the building from a nearly abandoned eyesore into permanent housing for over 200 seniors. A Senior Center on the second floor of the hotel was added in 1977 which included a social service case management component. Project FIND purchased the building in 1979 but the struggle to make it fully habitable extended until 1995.

Ellen Baxter (center, front)

Meanwhile, Ellen Baxter was meeting with and following in the footsteps of the Fathers John. She formed a new nonprofit called the Committee for The Heights Inwood Homeless (CHIH)

(now called Broadway Community Services) designed to provide a secular model that garnered investment from every level of government.

In the early 80s, CHIH transformed an apartment building on West 178th Street into 55 units of supportive housing finally opening in 1986. While the St. Francis residences had relied on simple financing packages, renovation of this building, known as “The Heights,” required an extremely complex combination of funding sources, including a low interest HPD Participation Loan from the city (for capital and acquisition costs), a state Special Needs Housing Act grant, private bank loans and federal tax credits.

Ellen Baxter (center) and Tony Hannigan (third from right)

Operating costs for The Heights were subsidized through a new federal subsidy which provided rental support for low-income tenants. But the Heights introduced another innovation: the notion of partnering with another non-profit to provide onsite services. Those were to come from a partnership with Columbia University Community Ser-vices (now called the Center for Urban Community Services, or CUCS).

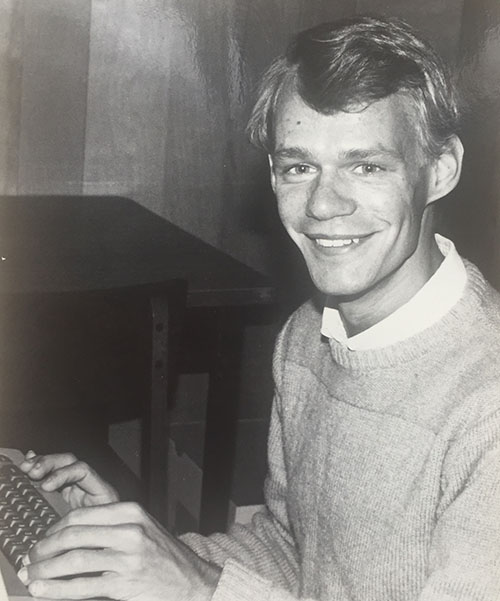

Tony Hannigan (left)

CUCS President & CEO Tony Hannigan’s story began a few years out of graduate school in 1981 when, he was tasked with a field initiative of locating vulnerable homeless single people stay-ing in SROs – and remembers that 40% of SRO housing stock had been lost to gentrification at that time. As Ellen was working on transforming the Heights, CUCS applied to the Department of Mental Health to provide services to the tenants.

Stephan Russo (left)

Another motivating force behind the birth of supportive housing was coming from communities’ desire to preserve and revitalize what they perceived as rapidly disappearing affordable housing. Thus, in 1981, when the West 87th Street Block Association heard that a deteriorating SRO, Capitol Hall, might be replaced with luxury housing, they approached Goddard Riverside Community Center and The Settlement Housing Fund to help preserve it. Goddard purchased the property in 1983 and started rehabbing it the following year into 202 supportive housing units.

Laura Jervis

Meanwhile, also on the Upper West Side, Laura Jervis was doing outreach to elderly people living in SROs there, having recently graduated from seminary. The now-retired West Side Federation for Senior and Supportive Housing (WSFSSH) Executive Director witnessed first-hand the fear people had to leave their rooms and the impact of isolation on elderly communities. She formed a coalition of community groups and religious institutions from the West Side to help these individuals, and WSFSSH was born. Their first building was The Marseilles, which Laura insisted on staffing with a social worker. “It’s hard to imagine today, but having social services on-site in senior housing was a radical idea in 1980!”

Laura Jervis (left)

Laura Jervis maintains that seniors and those who have experienced the trauma of homelessness need more than just housing, her advocacy message from the start. “Over the years, in all of our buildings, it is the sense of community that is developed by residents and staff that has been the key to the success of our mission.”

John Tynan (left)

Among the most ambitious and prolific early adopters of supportive housing in the early 80s was Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens who melded their mission of serving the most vulnerable and combined it with the Church’s sig-nificant real estate portfolio by convert-ing three vacant schools and a convent into 225 units of supportive housing called Caring Communities. The organization put together twelve separate funding sources to finance the project, including an HPD Participation Loan, federal Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation rental support and state Homeless Housing Assistance Program funding.

Another significant contribution from Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens was as a crucible for a genera-tion of powerful advocates: Executive Director John Tynan had the great good fortune to have Bill Traylor, Connie Tempel and Laura Mascuch all working for him in housing development or management.

Connie Tempel (second from right)

As these buildings were opening, how-ever, the question of who could live in them came to the forefront. Thus, in the mid-80s, Stephan Russo of Goddard Riverside Community Center called together other early pioneers to ensure that homeless neighbors and community members were going to continue to be served in this new model of housing, leading to the now-normal 60/40 mix of individuals referred from the shelters and low income individuals from the community. The coalition became the SRO Providers Group, which then met regularly to share promising strategies and to lobby city and state government in a single, unified voice. The SRO Pro-viders Group evolved into the Supportive Housing Network of New York.

Although the initial nonprofits miraculously succeeded in spite of no government support, the emergence of new federal, state and local funding programs starting in the mid-1980s resulted in the popularization of the supportive housing model. The passage of federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit legis-lation in 1986, for example, provided the opportunity for private investors to receive tax breaks in exchange for direct investments in low-income housing. Intermediary organizations like the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), the Corporation for Supportive Housing and Enterprise Community Partners have played a pivotal role in helping nonprofit developers across the country syndicate these credits, thereby generating much-needed equity for projects. The early role of government partnering has been crucial to the movement’s growth.

In 1988, New York established the SRO Support Subsidy Program to provide flexible services funding to nonprofit operators of SRO housing. The SRO Support Subsidy Program—now part of New York State Supportive Housing Program—currently assists supportive housing units throughout the state.

A significant joint initiative between the state and the city was then signed in 1990 to create thousands of new units of supportive housing for the homeless mentally ill. Called the “New York/New York Agreement,” this program successfully ensured the construction financing and ongoing operation of new projects to address the needs of homeless persons with psychiatric disabilities and was eventually expanded into the model we have today that serves multiple homeless populations with varying disabilities.

Bill Traylor

Bill Traylor remembers his early work at Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens being about community with and among people. His mentorship from Ellen Baxter and Laura Jervis centered on learning from the tenants themselves; not imposing upon them what they needed. This person-centered orientation was a revolutionary ethic that became the bedrock of creating sustainable community and brought out the concerns, needs, desires and hopes of the most vulnerable New Yorkers. The expertise and knowledge of homeless communities was valued.

Bill Traylor (right)

Traylor states, “It’s not doing to or doing for; it’s healing and being healed.” Remaining faithful to the original mission as a community of care is the root of the movement’s present-day success.

We at the Supportive Housing Network of New York are honored to celebrate the men and women whose extraor-dinary compassion, intelligence and rock-solid determination led to the creation of supportive housing. Their work served as the cornerstone of a now-national movement and, here in New York, laid the ground work for the creation of 50,000 supportive housing opportunities across New York State and commitments for another 35,000 units over the next fifteen years – the model’s beating heart of caring and re-spect is these pioneers’ enduring legacy.